OPUS DEI - TROJAN HORSE OF LIBERALISM IN THE CHURCH (PART VI)

|

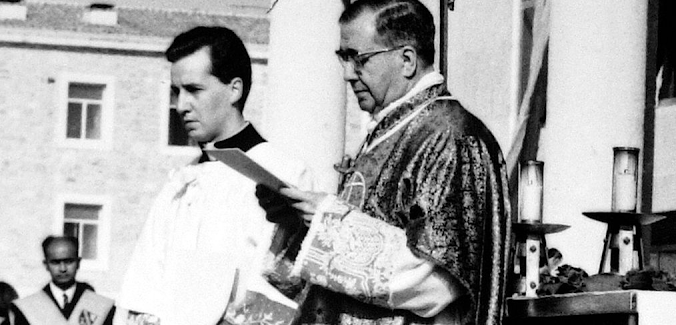

| Escriba y Albás during his infamous homily delivered at the University of Navarra, October 8, 1967, appropriately titled by Opus Dei themselves, "Passionately Loving the World". |

Part I - A Jewish Branch of Freemasonry?

Part II - Secularism and Liberalism: the Twin Pillars of the Work

Part III - Work as Means of "Sanctification"

Part IV - Opus Dei: "Reconciling" the City of God and the City of Man

Part V - The Work: Precursor to Vatican II

Escriba: a “vocation” to the world,

not to Christ’s priesthood

“No man can serve two

masters. For either he will hate the one, and love the other: or he will

sustain the one, and despise the other.” Matthew 6:24

Escriba himself

declared: “I NEVER thought of becoming a priest, or of dedicating myself

to God. That problem had never presented itself to me, because I thought it

was not something for me. What is more: the thought of possibly becoming a priest

someday BOTHERED me, in such a way that I felt myself an anticlerical.”

[1] We have clearly highlighted “never” in Escriba’s own “confession”:

that is, he never had a vocation to

the priesthood – neither at a point in time long before entering the priesthood

or immediately before – and what is more such a thought bothered him. Escriba, the self-described anti-clerical in his

youth, did not appear to overcome either this mind-set or improve his spiritual

life by the time he set upon his ecclesiastical career: “when the Lord willed that I should begin

working in Opus Dei, I did not have a single virtue, or a single peseta [Spanish currency].” Here, he

somehow links his decision to enter the seminary with the founding of Opus Dei,

even though this was still some years in the future. The point is, his

“vocation” – which was no real vocation – only

acquired “meaning” to him retrospectively

in his later decision to found the Work with its lay mentality. Which is to

say, to him, the priesthood only acquired meaning from a secular perspective, when he realized that he could utilize it as a means

to fully embrace the world via his “Work”. It is clear that before his

priestly ordination, Escriba never

envisaged himself becoming a Catholic priest in the commonly understood of the

word: “I realized that that was

not what God was asking me: I did not want to be a priest, to be the priest

– ‘el cura’ – as they say in Spain.…

I did not desire for myself such a priesthood.” [2] Thus, with no real

Catholic vocation, he entered the seminary through other ulterior motives as we

will see shortly.

Alas, his time in the seminary did not seem to be spent trying to

overcome his anticlericalism and grow in the virtues – above all, humility –,

and indeed one of his seminary professors during the academic year 1920-21

noted that he was a “fickle and proud” student who had to be reprimanded for

quarrelling. [3] Don Carlos Albás, Escribá’s uncle, who intimately knew his

nephew, and therefore, his interior spiritual disposition, refused to attend

his nephew’s first mass celebrated in 1925, despite the fact that this is traditionally

a key event gathering the new priest and his most intimate connections. [4] Those

who knew him in his youth found him a closed, mediocre character showing little

interest in things. [5] Former numerary Miguel Fisac, who had known intimately

the “Father” since the earliest days of the Work (and despite this was

forbidden from testifying before the “beatification” process), recalled details

in accordance with this general picture, noting his somewhat careless attitude,

and that – quite in accordance with his lay, worldly outlook – he “liked to

sing frivolous songs.” [6]

Most seemed to agree that Escriba had a certain tendency towards

self-idolatry, which throughout his life expressed itself in a latent – and

not-so latent – pride that occasionally expressed itself quite explicitly. Perhaps

this was most paradigmatically expressed when the “Father” told a gathering of

students in London, “I have known several popes, you all know numerous bishops,

but you have only known a single ‘founder’

and God will call you to account for having lived in the time of the ‘Father’.”

[7] When the Count of Barcelona, Don Juan de Borbón visited the “Father” in his

mansion in Rome, Escriba showed him the prominent place – somewhat set apart

from the rest – in the chapel where he offered this “prayer” to God daily: “Lord, Josemaría has done much for the Church.”

(!) [8] A certain scene in Luke’s Gospel of two opposing figures offering their

prayers to God – one humble and contrite, the other pharisaical and proud,

leaving the Temple unjustified – easily comes to mind with this anecdote. Jaime

Peñafiel, who had known the “Father” and was even willing to keep silent on

certain of his faults for the sake of Christian charity, had this to say on

Escriba’s root sin: “José María

Escriba [y] Albás – and not ‘de Balaguer’, was a man possessed by the sin of

the [fallen] angels, which is none other than that of pride, in addition to

vanity, which made him renounce his maternal last name to differentiate

himself from the rest of his family with the same modest lineage, but also to claim the noble rank of Marquis of Peralta…”

[9]

According to the late Father of the Church, the Gallican St Caesarius of

Arles, humility and pride are the

distinguishing marks separating the citizens of the Heavenly City from those of

the Earthly one. Using the Augustinian imagery of the two Cities, in sermon no.

233 he stated that the humble one – Christ – builds the Heavenly, the City of

God, while the proud one – the Devil – builds the Earthly one, the City of the

Devil. Accordingly, the sons of God and the Devil are recognized according to

their humility or pride: “The sons of God

and of the devil are not distinguished from each other except through humility

and pride. Whenever you see a proud man, do not doubt that he is a son of the

devil; whenever you see a humble person, you should believe with confidence

that he is a son of God.” [10] With this in mind, Escriba’s well known

pride certainly does not place him in a favourable position with respect to the

two Cities. On February 14, 1975 in Venezuela before a gathering of his

followers, he made a startling statement that may even be an unwitting

admission about the nature of the “spirit” which had thus far led his life, a

“spirit” that would be in perfect conformity with his root sin. When asked

about his views regarding confession for children, he answered as follows:

“Bring the children over to God, before the devil enters into them. Believe me,

you will grant them a great blessing. I

say this from experience, from the experience of thousands and

thousands of souls, and from personal

experience.” This statement was made after he had lied through his

teeth saying he had spent, “many thousands

of hours confessing children in the poor slums of Madrid.” According to the

testimony of Fisac, he never once saw him in the company of any poor person. Moreover, such an

enthusiastic participation in the sacrament of penance as Escriba describes it

would virtually have been a fulltime occupation. Was Escriba saying, a few

short months before his death, that he knew from “personal experience” that the devil once had the chance to “enter into” his soul? [11]

The aforementioned Miguel Fisac thought that Escriba was forced to join

the seminary due to the financial circumstances of his family. [12] Escriba’s

father, in financial ruin, was unable to pay for the university costs of his

son, thus leaving the priesthood as the only available career path for his son.

Escriba, the anti-clerical, proud and lukewarm soul that had never entered the

seminary with a real vocation was clearly not disposed under such a set of

circumstances to adopt a humble spiritual disposition that would allow him to grow

in holiness. It is further not difficult to see that, in this context, a man

probably irritated and bored due to finding himself in a life situation he

never desired for himself, and for whom applying the fruits of a real vocation

was the farthest thing from his mind, would have naturally been drawn towards an

idea that seemed novel, exciting, and revolutionary drawn out of the heterodox,

modernist and liberal ecclesial milieu of his time. And as we have seen, the

arch-heretical Chardin’s Divine Milieu

could well have served as a prime source of inspiration for Escriba’s equally

heterodox “theology of work”. If one considers the regrettable spiritual state

of a liberal priest desperately in search of an “escape valve” to release the

full strength of the liberal and secular forces in the deepest recesses of his

heart with the help he doubtless received from “certain” connections who did

not have the best interests of the Church in mind, the rationale and impetus

for how something as heterodox as “Opus Dei” could ever have been conceived is

easier to understand.

In a talk, Escriba himself explained why he

decided to become a priest: “ ‘Why did I become a priest?’, he said

on the anniversary of his ordination, ‘Because I believed that in this way

it would be easier to fulfill the will of God, which I did not [yet] know.

Since some eight years before my ordination I had a premonition but I did not

know what it was, and I did not know until 1928. That is why I became a

priest.’ ” It is again clear from these words

that, as we have seen, the “Founder” never experienced a direct “calling” to

the priesthood, that is, he never experiencing a real Catholic vocation. He did

not become a priest as an end in itself, the outcome of a specific vocation and

call by God, but merely as a means

whereby he could attain something else,

which he “did not [yet] know” at the time either of entering the seminary or

even of becoming a priest! He did not know, or what is more likely,

flatly rejected the “will of God” for consecrated religious such as priests

– to act as channels of divine grace for the sanctification of souls – at the time of his first mass, which makes

the absence of his uncle Don Carlos Albás in that event all the more

understandable! What is more, by proposing to himself that the priesthood

was a mere means for attaining some

other higher goal of which he had some vague premonition, he is in fact

subordinating the priesthood to that higher goal. The ultimate “goal” for him

was not the priesthood in itself but that something

else which he alludes to without clearly specifying what it was. In reality,

this vague premonition is likely a description of his restless soul trying to

find some end other than the

priesthood that would fully satisfy his proud, worldly soul with its inherent

lay mentality and anticlerical outlook. And as the years progressed,

this vague notion of creating something big that would satisfy his

hyper-inflated ego and sense of self-importance must have gradually coalesced

into what became known as “Opus Dei”. Thus retroactively,

when he spoke those words we have quoted from 1973, despite the fact that the

priesthood is the highest vocation instituted by Christ, he effectively

described his “vocation” to Opus Dei as a much higher one. And following from

this principle, one observes that in practice, numeraries are often ordained

into the priesthood without them necessarily having a real vocation, since the

priesthood in Opus Dei is merely a means to some other higher ends.

Therefore,

everything now becomes clear: Escriba, who never had a vocation to the

priesthood, felt himself in his deepest marrow as a fully secular “ordinary

man” with a lay mentality, albeit one who had to be a “priest” as part of his

daily routine or “work”. Bernal himself in his hagiographical account of the

“Founder” confirms this: “And he also viewed the priestly ministry

as a professional, ordinary job, as a work of God.” [14] Because

for Escriba the priesthood was an accidental, not a substantial part of his

“vocation”, which ultimately was a lay one. This idea is very clearly expressed

by Bernal in this same work which we have already cited in part II but is most

appropriate to reiterate again at the conclusion of this study: “it is…clear

that in the mind of the Founder of Opus Dei, for us the priesthood is a

circumstance, an accident, because – within the Work – priests and the

laity have the same vocation. In Opus Dei we are all equal.” [15]

Thus his calls for both the laity and priesthood (which he conflated to a

degree dangerously close to that of the Protestants) to fully immerse

themselves in the world with a secular mentality and his “passionate” love for

the world. He thus did not feel that Christ had called him “out of the world” because he was of the world (cf John

15:19), a world which he tenaciously clung to with all the might of his

misguided “faith” and his heretical theology of “salvation through work”.

We

end this study with the following words by Escriba, uttered about a year before

his death to a gathering of laypeople, and serve as a fitting conclusion

confirming everything we have said about the core essence undergirding the

spirituality of “Saint” José María Escriba y Albás and his “Work”, a “Work” fundamentally based on gnostic-Kabbalistic

principles which is certainly not that of God: “MY VOCATION IS THE SAME AS

YOURS. I NEVER HAD ANY OTHER ONE. That is why, I do not offend consecrated religious…, if I

love you in a very special manner. It is

a particular obligation of fraternity.”

[16]

“But prove all things; hold fast that which

is good.” 1 Thessalonians 5:21; “Therefore,

brethren, stand fast; and hold the traditions which you have learned, whether

by word, or by our epistle.” 2 Thessalonians 2:15

“But though we, or an angel from heaven,

preach a gospel to you besides that which we have preached to you, let him be

anathema.” Galatians 1:8

“And you shall be hated by all men for my name's sake: but he that shall persevere unto the end, he shall be saved.” Matthew 10:22

REFERENCES

1. SALVADOR BERNAL, Monseñor Josemaría Escrivá de

Balaguer. Apuntes sobre la vida del Fundador del Opus Dei; Rialp, Madrid

1980, 6ª ed., p. 61.

2. Salvador Bernal, Mons.

Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer, Ed. Rialp, 1976, Pág. 59.

3. Opus

Judaei, p 84.

4. Opus

Judaei, p 84.

5. Opus

Judaei, p 85.

6.

MIGUEL FISAC, Dr. ARQUITECTO 20 años de estrecha

relación con Escrivá. Fuente: ODAN (Opus

DEI AWARENESS NETWORK, Inc.) 2000 https://www.opuslibros.org/escritos/entrevista_fisac.htm

7.

Opus Judaei, p 109.

8.

Opus Judaei, p 107-8.

9.

Opus Judaei, p. 144.

10. The

Fathers of the Church – St. Caesarius, SERMONS, Volume III, The Catholic University of America, 1972, p 194.

11. Peter Berglar, “Apuntes”, Chapter 3: “La Fundación del

Opus Dei”, section 2. Y EL FUNDADOR DEL OPUS DEI SIGUIÓ TRABAJANDO.

12. MIGUEL FISAC, Dr.

ARQUITECTO 20 años de estrecha relación con Escrivá. Fuente: ODAN (Opus

DEI AWARENESS NETWORK, Inc.) 2000 https://www.opuslibros.org/escritos/entrevista_fisac.htm

13. Tertulia, 28-III-1973, Meditaciones IV, pág. 279.

14. Salvador Bernal, Josemaría

Escrivá de Balaguer – Apuntes sobre la Vida del Fundador del Opus Dei, Chapter

2: “Vocación al Sacerdocio”. 3. Alma Sacerdotal y Mentalidad Laical.

15. Bernal, Ibid.

16. SALVADOR BERNAL, Monseñor Josemaría Escrivá de

Balaguer. Apuntes sobre la vida del Fundador del Opus Dei; Rialp, Madrid

1980, 6ª ed., p. 104.

Comments

Post a Comment